In the 1960s, Algiers was a beacon for worldwide liberation movements. What happened to its rebellious spirit?

Amilcar Cabral, the leader of the Bissau-Guinean armed struggle against colonial Portugal, once said about Algiers: “The Muslims make the pilgrimage to Mecca, the Christians to the Vatican, and the national liberation movements to Algiers.” Cabral was also the first to name Algiers “capital of revolutions” in 1969. By the early 1970s, Algeria had a full blown authoritarian regime and left internationalism was on the retreat. Though Algiers is again the site of protest and young Algerians link their struggles against the government with protests against neoliberalism elsewhere in the world, the global city celebrated by Cabral is now a thing of the distant past.

Algeria’s independence in 1962 from France correlated with the fall of the French Fourth Republic and its colonial empire. After 132 years under French colonialism, the renascent yet limping Algeria had a population of 9 million people but only 500 university graduates. Algeria lacked reliable economic and political infrastructures—with France still showing vivid interest in its oil-rich desert in the south. Ninety percent of Algerians were illiterate; but they had brought the world’s fourth largest military power to its knees.

It was with this revolutionary spirit that in the early 1960s, the capital Algiers became a meeting ground for international civil rights activists, revolutionary intellectuals, artists and guerilla fighters, all of whom had taken a common stance against imperialism and colonialism.

The new government built a nation out of a looted colony. First president, Ben Bella, and the FLN, the ruling party that had mainly led the War of Liberation (1954-1962), dreamed of making Algeria an esteemed country in the international arena, notably by leading the Non-Aligned Movement, the loose alliance of newly independent countries that wanted to chart a future outside the influence of either the US, the Soviet Union or China.

At the founding conference of the Organization of African Unity (now the African Union), Ben Bella argued that the newfound anti-colonialist organization should provide help to liberation movements with arms, training and funding. “Let us all agree to die a little so that the people still under colonial rule may be free and African unity may not become a vain word,” he declared.

South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC) was the first resistance movement to be hosted in Algeria, establishing its international bureau in downtown Algiers in 1963. The ANC’s political ties with the FLN dated back to 1960, when ANC fighters trained alongside Algeria’s Liberation Army in Oujda, Morocco, following the Sharpeville massacre that resulted in the anti-apartheid movement’s turn towards armed struggle. Nelson Mandela, who took part in the trainings, stayed in Oujda until the summer of 1962. He was arrested as soon as he returned to South Africa, perceived by the apartheid government as a looming menace to public order, with an accusation, in part, of having trained alongside National Liberation Army (ALN) fighters. When he returned to Algiers in 1990, in his first visit abroad after his release, Mandela attested, “The Algerian army made me a man.”

Other liberation movements, such as Mozambique’s FRELIMO and the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), soon joined the new land of the damned, establishing bureaus not so far from one another in the capital’s main streets. Their abrupt arrival was moreover encouraged by Che Guevara’s iterative visits, which he took to in July 1963, the month that also marked the country’s first independence anniversary.

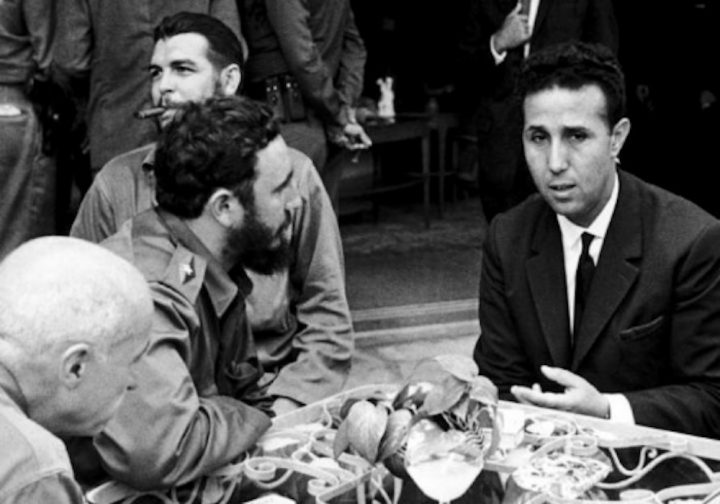

In October 1963, a war broke out between Algeria and Morocco, over the latter’s claims that territories in western Algeria were historically its own. Cuba intervened militarily alongside Algeria, and Morocco ultimately ceded its demands. (The Sand War, as it’s now known, resulted in the closure of borders between the two countries, which remain to this day.)

Cuba’s ties with Algeria were categorically, however briefly, strengthened. With Ben Bella’s laissez-faire attitude, Guevara aspired to contribute in making Algiers a base for worldwide movements. Guevara helped create an African Liberation Committee in Algiers in 1965. The Committee’s first mission was to assist Congolese rebels against the Belgian-backed and US-allied regime of Joseph Mobutu—a conflict stirred after the assassination of Patrice Lumumba in 1961. Guevara partook in an armed expedition himself, traveling in disguise to avoid the CIA’s notice. The fighters were divided into two fronts: one that landed in Brazzaville, west of DRC, while the 150-member strong second contingent, including Guevara, landed in Tanzania with a group of 14 Cubans, aiming to support Lumumba’s rebellion against Mobutu. They crossed Lake Tanganyika to DRC in April. Soon the Cuban presence was disclosed when four Cubans were killed during a conflict in June, and Che Guevara was summoned to leave—even by the fighters on his side—when the US and Mobutu stepped up the crackdown. (Che Guevara stayed in Tanzania afterward, where he started writing his Diaries of the Revolutionary War in Congo, before leaving for Latin America, never to return to Africa again.)

In June 1965, Colonel Boumediene (Mohammed Boukharouba was his real name) overthrew Ben Bella. Boumediene subsequently abolished Algeria’s constitution and ruled through a “revolutionary council,” which he implemented at his own advantage more than a decade after the revolution. Ben Bella was kept under house arrest until 1980, almost two years after the death of Boumediene.

A fervent proponent of anti-imperialism, Boumediene also coveted the vocation of making Algiers a vanguard for worldwide liberation movements. The number of bureaus held by international movements throughout Algiers grew significantly in the mid to late 60s, including even left-leaning, white movements like the Liberation Front of Québec (Canada) and the Breton Liberation Front (France).

Palestine’s Fatah (then the Palestinian National Liberation Movement) had its own recruitment and information office in one of Algiers’s busiest streets and stated that it had carried out several paramilitary trainings in the country’s south. Mozambique’s FRELIMO also claimed that some 200 of its men received guerilla fights trainings in the desert.

The country’s open-door policy welcomed guerilla fighters from Venezuela, Guatemala and Nicaragua, as well as individual expatriates from Tunisia, Morocco, Spain and Portugal, and from as far away as Brazil and Argentina. South Vietnam’s Viet Cong, Angola’s MPLA and Namibia’s SWAPO were also active in the capital.

In June 1970, when some 40 Brazilian political prisoners were to be exchanged for the kidnapped West German Ambassador to Brazil, they demanded to be flown to Algiers. Greeted with music and cigarettes—the Algerians knew the detainees’ yearning for nicotine—they were housed in pleasant bungalows in the suburban Ben Aknoun area, where some of them stayed until an amnesty was declared in Brazil almost a decade later. (The majority were members of the Popular Revolutionary Vanguard and the Movement of October 8, who had fled Médici’s brutal crackdown.)

Boumediene also didn’t shy away from openly antagonizing the United States. In 1967, he cut diplomatic ties with the US following the American-backed Six-Day War in which Israel tripled its territory by annexing the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and other Palestinian lands.

Israel’s victory was a major humiliation, and the streets of Algiers quickly filled with angered protesters who ransacked US representative institutions in the capital and called for the continuity of war against Israel. Boumediene, who had already sent troops to Egypt during the war, ordered sending more, but Egypt and the other Arab countries were not poised for another war shortly after their defeat. His wrath against the United States also rekindled Algeria’s support for the Vietnamese during the Vietnam War, and signaled to some American political activists they would be welcome in Algiers.

After being harassed by US security forces for opposing the Vietnam War and calling on black Americans to object to their induction into the US army, the Black Panther Party’s theorist and militant Stokely Carmichael fled to Algiers on September 6, 1967. “Here I am, finally, in the mother country,” he said upon arrival.

Eldridge Cleaver, one of the Panthers’ leaders, joined Carmichael in 1969. Cleaver was on the run after being charged with attempted murder in 1968 following a shootout with the police in Oakland, California. At first, Cleaver fled to Canada, then to Cuba hidden on a cargo boat, but he was soon compelled to leave Havana after Reuters disclosed his whereabouts.

By welcoming the Panthers, Boumediene further braved the wrath of the US. In Algiers, Cleaver was housed and received a monthly stipend to provide for his wife and small baby. He attended the opening of the first Afro-American cultural center of Algiers and became head of the International Section of the Panthers, which was exclusively created in Algiers in 1970. At a time where there was no US ambassador to Algeria (save a chargé d’affaires, who worked under the American Affairs section of the Swiss Embassy), Cleaver was officially recognized as the Black Panthers’ ambassador to Algiers. “This is the first time in the struggle of the black people in America that they have established representation abroad,” Cleaver said at the opening of the BPP’s subdivision.

Soon, Cleaver was involved with a number of other African liberation leaders who also sojourned in Algiers. Their binding of causes would lead to the creation of the Pan-African Festival, the first edition of which was held in Algiers in July 1969. The festival brought together South Africa’s Miriam Makeba and the American Nina Simone, among thousands of other artists and intellectuals from all African countries and African diasporas.

Boumediene’s support for the BPP initially appeared to know no bounds. In her 2018 memoirs, Elaine Mokhtefi, a white American writer married to an Algerian and who had worked alongside the Panthers as their fixer and interpreter during their heyday in Algiers, wrote that in 1969 Cleaver told her that he had killed a fellow American in Algiers named Clinton Rahim Smith, whom Mokhtefi also knew. Smith was planning to run away with the party’s money, Cleaver told her; but the victim was rumored to be involved with Cleaver’s wife, Kathleen, while Cleaver was on a visit to North Korea. Byron Booth, a fellow BPP member who accompanied Cleaver to Pyongyang, later admitted to witnessing the murder and burial of Smith’s body. Almost two years later, the Black Panther newspaper ran an article stating that Cleaver killed Rahim because of an affair the victim had with his wife. The article also accused Boumediene of “endorsing the crime.” The firearm used in the murder, an AK47, was a gift from North Korea’s Kim Il-sung, according to Donald L. Cox, then a BPP member who left the Panthers in 1971. Elaine wrote that she never spoke of it again, until in her 2018 memoirs, Algiers, Third World Capital. When the Algerian authorities found the body near la Pointe Pescade, west of Algiers, Cleaver remained free.

But changes were afoot in Algerian foreign policy. Algiers’ economy was starting to weaken and Boumediene was compelled to take to reforms. On February 24, 1971, Boumediene declared the nationalization of Algeria’s hydrocarbon industry (until then, most of the revenues went to French companies). The nationalization also marked the beginning of friendlier U.S.-Algerian ties that remain to this day. In October 2018, Chakib Khelil, a former Algerian minister of energy—controversial because of a corruption case and his relationships with US energy companies—declared that the US was involved in the 1971 nationalization.

The BPP was considered a serious security threat by the US government, and the FBI had already vowed to “neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for.” US companies now wanted in on oil and gas contracts that were up for grabs, and Boumediene’s regime, which was far more repressive against its own dissidents, started cracking down on the Panthers.

In 1972, members of the BPP-affiliated Black Liberation Movement hijacked a Detroit-Miami flight of 94 passengers, including the five hijackers who boarded with three children. The 86 passenger hostages were released in Miami, and the hijackers flew to Boston to pick up a ransom of $1 million—and a flight engineer who was qualified to fly overseas—before heading to Algiers in hopes of joining the BPP’s International Section. Upon arrival, Boumediene confiscated the ransom money and gave it back to the airline. (It had been the Panthers’ second hijack to be diverted to Algiers in less than two months.) Cleaver later published an open letter in which he complained that the Algerian leader had abandoned their cause. The next day, local authorities raided the Black Panthers’ villa, cut telephones and confiscated the party’s weapons and typewriters.

Algeria’s rapprochement with the US tolled the death knell of the Panthers’ presence in Algiers. In 1974, Boumediene landed in New York for the first time to attend a UN meeting, then went to Washington, where he met with President Nixon, although the two leaders’ countries had no diplomatic ties yet. (By then, Boumediene was not president yet, still ruling as Chairman of the Revolutionary Council.) But it was a clear indication of the direction Algeria was headed.

As Washington mended fences with Algiers, Algeria’s support for the movements only grew more circumspect over the years. Later, the country took to diplomatic action, pushing South Africa’s apartheid and the Palestinian question at the UN.

Today, streets like Boulevard Che Guevara, Rue Patrice Lumumba and Boulevard Amilcar Cabral often seem like the only reminders of Algiers’s forgotten history. Yet for the past year, as people have taken to the streets in the Hirak to protest a ruling elite that has ironically used the country’s liberation history to legitimize an unsatisfactory rule, the past has re-surfaced. “The Hirak is a cumulus of all the movements that Algeria has known,” said Toufik Ali Bey, a young activist and university student in Algiers. “Even if it is more oriented towards the ‘54 Revolution as an ultimate landmark, we still find inspiration in those liberation movements.”